“If civilization is to survive, we must cultivate the science of human relationships – the ability of all peoples, of all kinds, to live together, in the same world at peace.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt

Indus civilization, also known as the Indus valley Civilisationor Harappan civilization, is the earliest known urban culture of the Indian subcontinent. The nuclear dates of the Civilisation appear to be about 2500–1700 BCE, though the southern sites may have lasted later into the 2nd millennium BCE. Among the world’s three earliest civilizations—the other two are those of Mesopotamia and Egypt—the Indus Civilisationwas the most extensive.

Indus Valley Civilisation

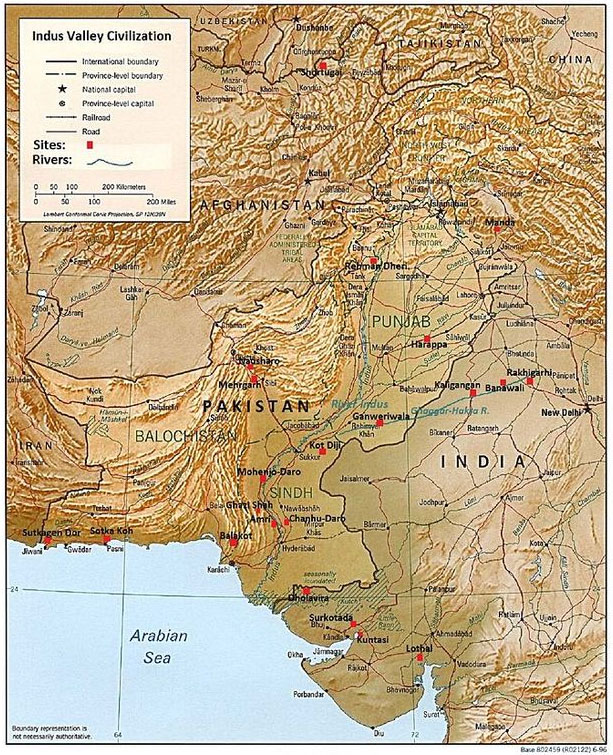

The Indus Valley Civilisation existed through its early years of 3300-1300 BCE, and its mature period of 2600-1900 BCE. The area of this Civilisation extended along the Indus River from what today is northeast Afghanistan, into Pakistan and northwest India.

The Indus Civilisation was the most widespread of the three early civilizations of the ancient world, along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were thought to be the two great cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, emerging around 2600 BCE along the Indus River Valley in the Sindh and Punjab provinces of Pakistan. Their discovery and excavation in the 19th and 20th centuries provided important archaeological data about ancient cultures.

Chronology

Sir Mortimer Wheeler, British archaeologist who is noted for his discoveries in Great Britain and India and for his advancement of scientific method in archaeology. After serving in World War II, Wheeler was made director general of archaeology for the government of India (1944–47), where his research focused on the origins and development of the Indus civilization.

Wheeler’s work provided archaeologists with the means to recognize approximate dates from the civilization’s foundations through its decline and fall. The chronology is primarily based, as noted, on physical evidence from Harappan sites but also from knowledge of their trade contacts with Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Lapis Lazuli was the only product that was immensely popular in both cultures and, although scholars knew it came from India, they did not know from precisely where until the Indus Valley Civilisation was discovered. Even though this semi-precious stone would continue to be imported after the fall of the Indus Valley Civilization, it is clear that, initially, some of the export came from this region. Various regions emerged at different phases of the Harappan civilisation, which projected a chronology of human advancement. These phases can be categorised as follows:

- Pre-Harappan – c. 7000 – c. 5500 BCE: The Neolithic period best exemplified by sites like Mehrgarh which shows evidence of agricultural development, domestication of plants and animals, and production of tools and ceramics.

- Early Harappan – c. 5500-2800 BCE: Trade firmly established with Egypt, Mesopotamia, and possibly China. Ports, docks, and warehouses were built near waterways by communities living in small villages.

- Mature Harappan – c. 2800 – c. 1900 BCE: Construction of the great cities and widespread urbanisation. Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro are both flourishing c. 2600 BCE. Other cities, such as Ganeriwala, Lothal, and Dholavira are built according to the same models and this development of the land continues with the construction of hundreds of other cities until there are over 1,000 of them throughout the land in every direction.

- Late Harappan – c. 1900 – c. 1500 BCE: Decline of the Civilisation coinciding with a wave of migration of the Aryan people from the north, most likely the Iranian Plateau. Physical evidence suggests climate change caused flooding, drought, and famine. A loss of trade relations with Egypt and Mesopotamia has also been suggested as a contributing cause.

- Post-Harappan – c. 1500 – c. 600 BCE: The cities were abandoned, and the people had moved south. The Civilisation had already fallen by the time Cyrus II (the Great, r.c. 550-530 BCE) invaded India in 530 BCE.

Discovery & Early Excavation

The story of the Indus Valley Civilization, therefore, is best given with the discovery of its ruins in the 19th century CE.

James Lewis (better known as Charles Masson, l. 1800-1853 CE) was a British soldier serving in the artillery of the East India Company Army when, in 1827 CE, he deserted with another soldier. In order to avoid detection by authorities, he changed his name to Charles Masson and embarked on a series of travels throughout India. Masson was an avid numismatist (coin collector) who was especially interested in old coins and, following various leads, wound up excavating ancient sites on his own. One of these sites was Harappa, which he found in 1829 CE. He seems to have left the site fairly quickly, after making a record of it in his notes but, having no knowledge of who could have built the city, wrongly attributed it to Alexander the Great during his campaigns in India c. 326 BCE.

When Masson returned to Britain after his adventures (and having been somehow forgiven for desertion), he published his book Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and Punjab in 1842 CE which attracted the attention of the British authorities in India and, especially, Alexander Cunningham. Sir Alexander Cunningham (l. 1814-1893 CE), a British engineer in the country with a passion for ancient history, founded the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1861 CE, an organisation dedicated to maintaining a professional standard of excavation and preservation of historic sites. Cunningham began excavations of the site and published his interpretation in 1875 CE (in which he identified and named the Indus Script) but this was incomplete and lacked definition because Harappa remained isolated with no connection to any known past Civilisation which could have built it.

In 1904 CE, a new director of the ASI was appointed, John Marshall (l. 1876-1958 CE), who later visited Harappa and concluded the site represented an ancient Civilisation previously unknown. He ordered the site to be fully excavated and, at about the same time, heard of another site some miles away which the local people referred to as Mohenjo-Daro (“the mound of the dead”) because of bones, both animal and human, found there along with various artefacts. Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro began in the 1924-1925 season and the similarities of the two sites were recognized; the Indus Valley Civilisation had been discovered.

In 1912, John Faithfull Fleet, an English civil servant working with the Indian Civil Services, discovered several Harappan seals. This prompted an excavation campaign from 1921-1922 by Sir John Hubert Marshall, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, which resulted in the discovery of Harappa. By 1931, much of Mohenjo-Daro had been excavated, while the next director of the Archaeological Survey of India, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, led additional excavations.

The Partition of India, in 1947, divided the country to create the new nation of Pakistan. The bulk of the archaeological finds that followed was inherited by Pakistan. By 1999, over 1,056 cities and settlements had been found, of which 96 have been excavated.

Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) contained urban centres with well-conceived and organised infrastructure, architecture, and systems of governance.

By 2600 BCE, the small Early Harappan communities had become large urban centres. These cities include Harappa, Ganeriwala, and Mohenjo-Daro in modern-day Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar and Lothal in modern-day India. In total, more than 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Indus River and its tributaries. The population of the Indus Valley Civilisation may have once been as large as five million.